Policy recommendations on LGBTIQ+: focus on ideals or feasibility?

31 July 2023 - The European UNIQUE-project attempted to introduce inclusion of LGBTIQ+ students in vocational education. At the end of the project, political recommendations were developed. Because there was little time left to consult experts face-to-face, it was decided to check the draft recommendations through a survey. To the surprise of the project partners, key recommendations were rejected by a substantial number of stakeholders. This raised the question whether policy recommendations on sexual and gender diversity in schools should be based on idealistic points on the horizon, or on more realistic short-term or mid-term objectives. The implications of this choice may be helpful or blocking future successful implementation of LGBTIQ+ interventions and policies.

Draft recommendations focusing on structural change

The UNIQUE project focused on teacher training and encouraging teachers to become ambassadors for LGBTIQ+ inclusion in their classes, institutions and beyond. The project was implemented in Greece, Cyprus, Croatia, Poland and in part in Bulgaria. These are not the easiest countries to implement LGBTIQ+ projects. Already during the project, it became clear that the UNIQUE-strategy faced many challenges. Some of the mainstream partners found it challenging to be explicit about the LGBTIQ+ focus of the project and preferred to integrate the topic subtly in the broader area of inclusion. When the teacher training was ready, some teachers were shocked to find out that the course was in fact about sexual and gender diversity and walked out angrily. In one country, an education department official published a homophobic meme on his personal Facebook wall, depicting gruesome claws in rainbow colors grabbing at innocent children.

Another challenge was the singular perspective that education, and especially vocational education, should be focused on transferring knowledge and training hard skills. GALE promoted to offer training on how teachers can deal with adverse emotions of students, which also implied attention for the positive or negative emotions teachers may experience themselves on this topic, or when being confronted with ‘difficult’ students or their parents. In many vocational schools, a focus on emotional intelligence and attitudes was considered unnecessary and unprofessional, even when all teachers would agree that client friendliness is a required skill for vocational students. And this anti-emotion perspective might a keystone of the entire education system, making it harder to overcome.

In the draft recommendations, these experiences were reflected by keeping the recommendations rather abstract (trying not putting off the homophobes and transphobes), but at the same time focusing at the need for structural change (eliminating heteronormativity in teaching and in institutional policies).

Resistance against cultural change

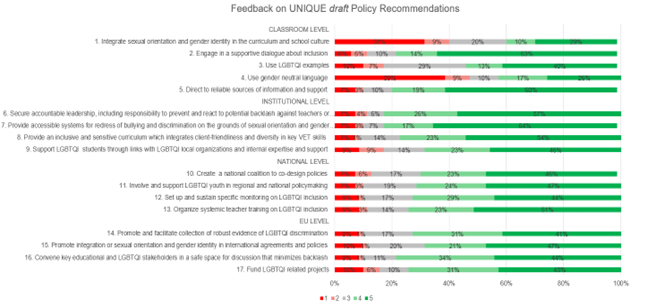

Because there was little time left to consult experts face-to-face, it was decided to check the draft recommendations through a survey. To the surprise of the project partners, some of the key recommendations were rejected by a substantial number of stakeholders.

- “Integrate SOGIESC in the curriculum and school culture” scored 40% disagreement and 20% doubt, with a minority of the respondents supporting this recommendation.

- “Use LGBTIQ+ examples in class” scored 17% disagreement and 29% doubt, leaving only 54% supporting it.

- “Use neutral and supportive language” (which was already a rather abstract formulation of not using sexist language and using proper pronouns) met with 47% disagreement and 10% doubt, leaving a minority supporting this.

These 3 controversial issues were part of the 5 recommendations on the classroom level. Because the intention was to build the recommendations on the institutional level, the national level and European level as directly as possible on the classroom level recommendations, this posed a real problem for the entire recommendations framework.

The partnership interpreted the disagreement with and doubt about these three recommendations as reflecting a broader resistance against changing regular routines and habits and against structurally changing school culture. The selected, already rather ‘friendly’ stakeholders were in principle willing to engage with sexual and gender diversity, but changing their regular routines substantially was too much to ask, even for them.

The dilemma: focus on ideals or feasibility?

The UNIQUE partnership was now confronted with the question whether the policy recommendations should be focused on ideals or on feasibility. Should we focus on suggestions for an ideal situation in vocational schools, or should we offer more moderate recommendations that link better with the current attitudes and willingness of the innovators and early adopters who have to engage with sexual an gender diversity in these less supportive countries and school cultures?

The partnership already was confronted with this earlier in the project, when we developed the online course for teachers. Some of the partners focused on linking into the type of education teachers were used to. Their units used academic language, were highly informational, but their concrete suggestions did not give attention to classroom contexts. Others were focusing on emotions, attitudes and how to overcome a sense of resistance. We labelled resistance as “limiting convictions” in order not to offend participants by calling their beliefs “prejudiced”. Some of the partners copied American-style concrete suggestions like asking for pronouns from the first lesson on, and various ways to promote explicit LGBTIQ+ visibility – which might not be implementable in less welcoming classrooms in the pilot countries. Other partners focused on more general suggestions (for example, on how to combat bullying and why specific attention was needed for gender and sexuality in this) and on concrete interventions that were more low-key and hopefully less controversial.

The partnership did not find a way out of this dilemma. The choice was not only dependent on principles, but also on social pressures. On one hand there were pressures by teachers and institutions, which were partly originating in limiting convictions. On the other hand there were pressures of LGBTIQ+ NGOs and experts, pressing for political correctness and proposing long-term goals even when these would not be feasible on the short term. For LGBTIQ+ NGOs, limiting their demands could feel like a slap in the face and even as homophobia or transphobia because LGBTIQ+ students need radical change now . But at the same time we had to consider that stating our recommendations in a too ambitious way would drive potential allies away and might make any school change more challenging. It was difficult to find a mid-way between the two extremes.

Working solution

As a working solution, GALE (the editor of the recommendations) decided to reformulate the original recommendations into 4 themes, that were repeated on the classroom, institutional, national and European level.

The four themes are:

- Emotional intelligence: attention for emotions and attitudes is necessary to sustain real change in relation to sexual and gender diversity, but the way this is implemented depends on the context. When teachers are used only to top-down informational or technical skill-based teaching, the trainers need to be sensitive to how they can coach vocational teachers to acquire sensitive attitudes and skills. Especially for when they have to handle adverse emotions in class.

- Visibility: LGBTIQ+ issues are part of the broader way people deal with sex, gender and diversity, but just dealing with diversity or inclusion in general will not have the required impact on LGBTIQ+ inclusion. Due to the limiting convictions of some stakeholders, the level and type of visibility need to be tailored to the context.

- Integration: treating sexual and gender diversity as a specific topic will make it special and that can have a counterproductive effect on students. We don’t want to make it a special, but a common aspect of life. Therefore, and also for the sustainability of the type of attention, it needs to be fully integrated in the curriculum and policies of the vocational institute. Good integration does not have to be substantial in time but it has to be substantial in quality.

- Innovation: we cannot expect that vocational institutions or other schools will implement LGBTIQ+ inclusion and attention for sexual and gender diversity overnight. There will always be innovators, early adopters, friendly and conservative people in the team. And there will always be laggards who will never agree with any change. Good innovation requires innovation leaders to gradually win over the hearts of each of these subgroups of the team. In the beginning, you work with innovators and early adopters, but you leave laggards alone. This requires a sensitive and strategic approach. A strategic approach does not imply a weak on non-principled attitude of the change leaders; it is a necessary realism to make progress.

In the final publication of the UNIQUE-recommendations, the four key topics are worked out to each level and on each level more practical suggestions are given on how to implement a high impact strategy. Each of these concrete suggestions is accompanied with some considerations about how teachers and school managers can choose an appropriate strategy, depending on their context. This leaves the final decision on what and how to implement to the tailoring by the local stakeholders. This may be challenging for external consultants or advocates, but we need to recognize that internal commitment to school change is of key importance.

Peter Dankmeijer

Sources: Focus on feasibility or on ideals. The development of needs based policy recommendations for LGBTIQ+ inclusion by the UNIQUE project. and The UNIQUE-Project Policy Recommendations